In the quiet hum of a modern kitchen, an invisible dance of physics transforms cold metal into a cooking surface. This phenomenon, known as electromagnetic induction heating, represents one of the most elegant applications of fundamental scientific principles to everyday life. At its core lies the clever manipulation of magnetic fields and electrical currents to generate heat directly within cookware, bypassing traditional methods of thermal conduction. It is a technology that feels almost like magic but is firmly rooted in the groundbreaking work of Michael Faraday, whose discovery of electromagnetic induction in the 19th century laid the foundation for this revolutionary cooking method.

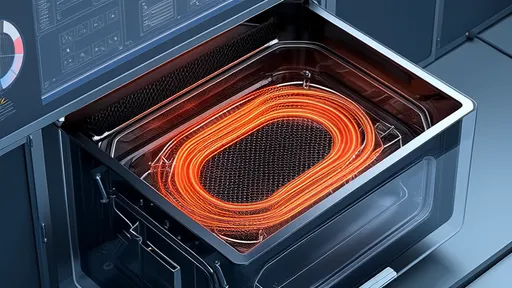

The entire process begins with the cooktop itself, which contains a tightly wound coil of copper wire. When an alternating electric current courses through this coil, it generates a dynamic, oscillating magnetic field that extends above the glass surface of the induction hob. This field is the invisible engine of the system, a force constantly shifting in direction and strength, poised to interact with any suitable material placed within its influence. It is this interaction that separates induction cooking from all other forms, as the heat is not generated by the cooktop but by the cookware itself.

For the magic to happen, the cookware must be made of a ferromagnetic material, typically iron or certain types of stainless steel. When such a pot or pan is placed on the induction zone, the rapidly alternating magnetic field penetrates the metal. According to Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction, this changing magnetic field induces circulating electric currents within the metal itself. These currents, known as eddy currents, swirl through the base of the cookware like miniature whirlpools of electricity, encountering resistance as they move through the metal's crystalline structure.

It is this resistance that becomes the true hero of our story. As the eddy currents fight their way through the metal, their kinetic energy is converted into thermal energy through a process known as Joule heating. The same principle that causes a traditional wire element to glow red-hot is at work here, but with a crucial difference: the heat is generated internally throughout the material rather than being applied externally. This results in incredibly efficient and rapid heating that can bring water to a boil in nearly half the time of conventional electric or gas stoves.

The efficiency of this energy transfer is nothing short of remarkable. While gas cooktops typically operate at around 40% energy efficiency and traditional electric coils at approximately 75%, induction hovers consistently between 84-90% efficiency. This means that almost all the electrical energy drawn from the outlet is converted into usable heat within the cookware, with minimal waste. The surrounding air and cooktop surface remain relatively cool, making induction not only efficient but also safer than alternative cooking methods.

This remarkable efficiency stems from the direct nature of the energy transfer. In conventional cooking, heat must travel from a burner through the cookware bottom and then into the food, with losses occurring at each transfer point. With induction, the magnetic field essentially bypasses the intermediate steps, turning the cookware base into an instant heating element. The responsiveness is equally impressive – when the power level is adjusted, the magnetic field changes immediately, providing control that rivals gas cooking without the open flame.

The design of induction-compatible cookware plays a crucial role in this process. Manufacturers must carefully consider the material composition, thickness, and even the flatness of the cooking surface. The base must contain enough ferromagnetic material to allow sufficient eddy currents to form, typically requiring a minimum thickness of 2-3 millimeters. Some cookware features layered bottoms with an iron or steel plate sandwiched between other materials to ensure compatibility while maintaining other desirable properties like even heat distribution or lightweight construction.

Beyond the kitchen, electromagnetic induction heating finds numerous industrial applications that leverage the same fundamental principles. Metal treatment facilities use powerful induction heaters for processes like annealing, hardening, and brazing, where precise, localized heating is required. Manufacturing plants employ induction for melting metals in foundries, while electronics factories use miniature induction systems for circuit board soldering. Even the medical field utilizes induction heating for sterilization processes where clean, precise thermal control is essential.

As we look toward the future of cooking technology, induction heating continues to evolve with smarter controls, more flexible cooking zones, and integration with home energy systems. The development of induction hobs that can work with any type of cookware, not just ferromagnetic materials, represents the next frontier in this technology. Researchers are exploring ways to use different frequencies and coil configurations to induce currents in a wider range of materials, potentially revolutionizing the technology once again.

What began as a laboratory curiosity in Faraday's time has transformed into one of the most efficient and precise cooking methods available today. The elegant dance between magnetic fields and metal continues to captivate physicists and chefs alike, representing that rare convergence where deep scientific understanding meets practical daily application. As this technology continues to spread through kitchens worldwide, it carries with it the legacy of scientific discovery and the promise of even more innovative applications to come.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025