In the quiet hum of a home kitchen, where flour dusts the air like winter’s first snow and the warm scent of vanilla promises comfort, a silent revolution has been unfolding. For decades, bakers—both amateur and professional—have debated the merits of measuring by volume versus weight. The casual scoop-and-sweep of a cup of flour seems a world away from the precise digital readout of a kitchen scale. Yet, as the art of baking meets the rigor of food science, a compelling narrative emerges: the accuracy of your kitchen scale is not merely a detail; it is the very foundation upon which baking success is built.

The heart of this story lies in understanding what we are truly measuring. Baking is, at its core, an edible chemical reaction. It is a delicate dance of proteins, starches, leavening agents, and liquids, choreographed by heat. The ratios of these ingredients are not suggestions; they are the recipe’s genetic code. A bread dough requires a specific hydration level to develop the gluten network necessary for a chewy, open crumb. A cake batter demands a precise balance of flour, sugar, and fat to achieve its signature tender texture. Even a minor deviation can alter the outcome dramatically. This is where the volumetric method, the beloved cup measurement, reveals its fundamental flaw: inconsistency.

Consider the humble cup of all-purpose flour. The way one person fills that cup can vary astonishingly. The scoop-and-sweep method can pack anywhere from 120 to 150 grams of flour into that same vessel. The spoon-and-level technique offers more consistency but is still prone to human error and interpretation. One baker’s “level” is another’s “heaping.” This variance might seem trivial—a tablespoon more or less—but in the precise world of baking percentages, it is a seismic shift. That extra tablespoon of flour could turn a soft, moist cookie into a dry, crumbly biscuit. It could mean the difference between a lofty, well-risen cake and a dense, sad slab.

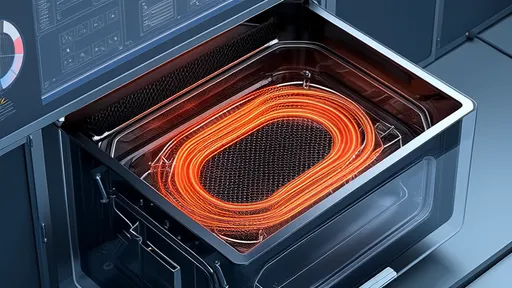

This is the void that the digital kitchen scale was designed to fill. By shifting the paradigm from volume to mass, we eliminate the variable of human technique. 150 grams of flour is always 150 grams, whether it was scooped, spooned, or poured. This objective consistency is the first and most crucial step toward reproducible results. But not all scales are created equal. The market is flooded with devices boasting different levels of precision, typically measured by their readability and accuracy.

Readability refers to the smallest increment a scale can display. For most serious baking, a readability of 1 gram (0.1 oz) is considered the gold standard. This level of precision allows a baker to measure minute quantities of potent ingredients like salt, yeast, or baking powder with confidence. A scale with a readability of only 5 grams might round a 2-gram measurement of instant yeast up or down, introducing a potential error of over 100% for that ingredient. This error then ripples through the entire recipe, potentially over- or under-fermenting a dough, leading to poor oven spring or off-flavors.

Accuracy, however, is the scale’s ability to tell the truth. A scale might be readable to 1 gram, but if it is poorly calibrated, it could be consistently off by 5 or 10 grams. This is a silent failure, far more dangerous than the obvious inconsistency of cup measurements because it breeds a false sense of security. A baker, trusting their precise tool, would have no reason to suspect their 500 grams of flour is actually 510 grams—a 2% error that could be the downfall of a delicate French macaron or a laminated croissant dough where hydration is everything. The relationship between a scale’s precision and the baker’s success rate is therefore not linear but exponential. High precision provides the potential for high success, but only if that precision is married to true accuracy.

The impact of this precision-accuracy duo is most visible in the most technically demanding bakes. Take sourdough bread, a pursuit that has captivated home bakers in recent years. A typical recipe might call for 500 grams of bread flour, 350 grams of water, 100 grams of active sourdough starter, and 10 grams of salt. This creates a dough with a 70% hydration level. Now, imagine a scale with poor accuracy consistently adds an extra 7 grams of water. The hydration level sneaks up to 71.4%. This 1.4% change might not sound like much, but in a high-hydration dough, it can be the difference between a dough that is slack and manageable and one that is a sticky, unworkable mess on the countertop, unable to hold its shape during proofing.

The same principle applies to the delicate ecosystem of pastry. French pâte à choux, the airy pastry used for éclairs and cream puffs, is a notorious diva. Its structure relies almost entirely on steam leavening, which is created by the precise gelatinization of starch in a specific ratio of flour, water, butter, and eggs. Too much flour, and the paste becomes too thick, unable to expand properly. Too much egg, and the batter becomes too loose, spreading instead of puffing. A miscalculation of just a few grams can lead to a pan of flat, eggy disappointments instead of light, hollow puffs ready to be filled with cream.

Beyond the technical failures, there is a more subtle, yet equally important, benefit to precise measurement: the development of intuition and skill. A beginner baker following a recipe with cups may experience a series of frustrating, inconsistent results. They are unable to isolate what went wrong because the independent variable—the ingredient amount—was never truly controlled. Was the cake dense because the oven temperature was off, the leavener was old, or because they inadvertently used too much flour? They cannot know. This trial-and-error process becomes a game of chance, hindering the learning process.

Conversely, a baker using a precise scale removes that major variable from the equation. Success and failure become clearer lessons. A failed bake can more reliably be attributed to technique—kneading time, fermentation temperature, oven hot spots—rather than recipe ambiguity. This accelerates the baker’s education, allowing them to hone their skills with the confidence that the formula itself is sound. The scale becomes not just a tool for measurement, but a tool for learning. It transforms baking from a mysterious art into a learnable, repeatable science.

For the home baker looking to elevate their craft, the message is clear. Investing in a high-quality digital kitchen scale—one with a readability of 1 gram and a reputation for accuracy—is the single most impactful upgrade they can make to their kitchen arsenal. It is more important than a stand mixer, more crucial than a convection oven. It is the key that unlocks consistency, demystifies failure, and paves the way for true culinary creativity. After all, one must first master the rules before they can artfully break them. In the measured world of baking, success isn’t just about following a recipe; it’s about knowing, with unwavering certainty, that your foundation is solid.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025